- Home

- Sophie Schiller

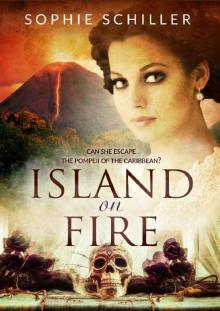

Island on Fire

Island on Fire Read online

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, organizations, places, events, and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

No part of this work may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher.

Published by Kindle Press, Seattle, 2017

Amazon, the Amazon logo, Kindle Scout, and Kindle Press are trademarks of Amazon.com, Inc., or its affiliates.

Contents

Map

Part 1

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Part 2

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Part 3

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Author’s Note

Bibliography

Part 1

Chapter 1

Monday, April 21, 1902

Saint-Pierre, Martinique

The city of Saint-Pierre was in a joyous mood. It was the end of the sugar harvest, a time for celebration and revelry. Music and laughter filled the air. The stars lit up the heavens, and the moon shone resplendent over the bay, where schooners and steamers lulled gently in the breeze. The strains of biguine music echoed from the cabarets, and the odor of piquant Creole cooking wafted from the cafés that lined the waterfront. No one noticed that on the summit of Mount Pelée, a thick plume of black smoke was rising steadily, growing larger by the minute.

In a villa nestled on the slopes of the mountain, Emilie Dujon felt the earth trembling. A picture rattled against the wall, and a lizard scampered away in fright. A rumbling noise that sounded like distant thunder drowned out the crickets and tree frogs. Startled out of her reverie, she dropped her copy of The Mysterious Island and grabbed her binoculars. Focusing them on the summit, her eyes widened in surprise. Smoke and steam were rising from the lower crater, the one they called the Étang Sec. It grew in size and curled outward, like an enormous gray mushroom, before blowing leeward over Saint-Pierre.

Emilie lowered the binoculars and scanned the mountain for several minutes, feeling a clenching pain in her gut. A young woman of nineteen with amber eyes, chestnut-colored hair, and a grave but lovely face, she had been watching these occurrences almost daily, and now they were becoming more frequent and, by the looks of things, more serious. For years the experts had claimed Mount Pelée was extinct, but if that was the case, why was there so much ash and smoke?

She made a note of her findings in a notebook, and sat down in front of her vanity mirror to brush her hair and reflect on the matter. Emilie was by nature very observant. She loved to study the world around her and uncover its mysteries. She spent long hours riding her stallion over the hills and valleys of Mount Pelée; exploring her tropical world was where she felt most at home. She had a good grasp of West Indian geography, having studied it at the convent school of Saint-Joseph de Cluny, and she knew that volcanoes were formed by subterranean fires deep below the earth’s crust. But a piece of the puzzle was still missing. Dead volcanoes do not emit clouds of smoke and ash. She wondered if there was something more to Pelée that the experts were not saying.

Tonight was supposed to be a happy occasion, a chance to forget her worries and enjoy herself. Her fiancé, Lucien Monplaisir, was taking her to a gala performance of La fille du régiment at the theater in Saint-Pierre, and she was thrilled. Normally Lucien had no patience for cultural events, but tonight he was making the sacrifice just for her. Emilie smiled, thinking how strange and wonderful it was to be in love. In the span of a few months, it had changed Lucien from a world-weary sugar planter into a refined gentleman. And soon she would be his wife. Just thinking about it sent a surge of warmth throughout her body, and she felt a tingling in her knees.

At eight o’clock, spectators arrived in top hats and tails and long muslin gowns and turbans knotted in the distinct Martinique fashion. While the musicians were warming up their instruments, a murmur of anticipation rose up to the private box seat where Emilie sat with Lucien and his younger sister, Violette.

Emilie was brimming with excitement. She smoothed out her muslin gown and gazed at her surroundings. This was her first trip to the theater in years. It was considered an unnecessary luxury ever since her father’s plantation, Domaine Solitude, started to lose money. The concert hall was even more splendid than she remembered. It shimmered like a golden Fabergé egg. The chandelier glowed, spreading warm light over the frescoes that adorned the ceiling. Gazing over at Lucien, her heart swelled with pride. She could scarcely believe how she, the daughter of a modest cocoa planter, had captured the heart of the richest sugar planter in Martinique.

The lights went down, and the play began. The audience watched with rapt attention, including Emilie, whose eyes scarcely left the stage. Even Lucien, who normally grew bored after only a few minutes, seemed to be enjoying himself.

In the middle of the third act, Emilie looked up and spied an old school friend, Suzette de Reynal, sitting in the opposite box. She seemed to be gazing over at Lucien. Emilie lifted her opera glass, and to her amazement, Suzette winked at him. Stunned, Emilie held up her program and saw out of the corner of her eye that Lucien met her gaze and winked back in return. For several minutes she watched the two of them engaged in silent communication. Clearly this was not the first time. Before long, Lucien got up and mumbled something about needing a drink. Panic spread throughout Emilie’s limbs, and her heart pounded. Surely it had to be a mistake. She got up and followed him outside, but Lucien was nowhere to be found. She searched for him through the crowd, and when she reached a potted palm, she froze. Ensconced behind the plant were Lucien and Suzette, locked in a passionate embrace.

Emilie’s face burned in anger. Time seemed to stand still. She took a few steps backward and fled to the safety of her seat. She willed herself to remain calm, but it took all the determination she could muster. Tears welled in her eyes. How could she have been so blind? How could she have been so naive? She blamed her own trusting nature. She was sure she had failed to see the clues that were there all along.

When Lucien returned to his seat, he put his hand on Emilie’s shoulder, but she stiffened at his touch. All at once, she lost interest in the play. She lost all interest in Lucien. And then a great feeling of dread came over her when she realized that the wedding invitations had already been sent out. Perspiration beaded on her forehead. She tried fanning herself, but nothing could quell the anxiety and dread that had taken hold of her.

In the midst of her turmoil, a great rumbling noise filled the hall. The chandelier swayed, and

the entire theater shook. Panic erupted in the audience. The rumbling noise grew louder, and the shaking intensified. The actors looked around in confusion. When a piece of scenery fell midstage, they shrieked and ran backstage in terror. And then, to everyone’s horror, a marble statue fell into the audience, giving rise to mass panic.

Emilie gasped in fright. Someone yelled, “Earthquake!” and all at once everyone jumped out of their seats and raced toward the exits. The musicians fled the orchestra pit like wasps from a burning nest, and the once-cheerful hall turned into mass hysteria. People were shouting and jostling each other in their haste to escape. An old woman cried out, and an elderly man in a black suit and tails struggled to protect her as they were shoved aside in the melee.

Lucien grabbed Emilie’s hand and said, “Come on, let’s get out of here.” He pulled her and Violette through the crowd, and they hurried down the marble staircase. They raced through the courtyard, down the stairs, and out to rue Victor Hugo, where the carriages were waiting. After they climbed inside, the driver proceeded north on rue Victor Hugo, dodging frightened residents and spooked horses. Emilie’s heart raced and she felt as if she was having a nightmare. Boom! An explosion like cannon fire rocked the carriage. In the distance, the mountain appeared to be glowing. The blast was followed by a loud rumbling noise and tremors that shook the earth.

The horses whinnied and reared, and the elderly West Indian driver struggled to control them. “Ho! Ho!” he cried, pulling on the reins. Emilie feared the ground would split open beneath them, swallowing them up. Even Lucien looked terrified. The gas lamps swayed, and roof tiles smashed to the ground. A swarm of people hurried past their carriage on their way to the cathedral, crossing themselves and uttering prayers out loud.

Emilie’s muslin dress was soaked with sweat. Heat and humidity hung in the air like a wet blanket. She glanced over at Lucien, but he was staring at the smoldering volcano with a mixture of fear and awe. Dear God, she prayed, please don’t let me die together with Lucien. Not here, not now. Shutters flew open as fearful residents peered out into the darkness. A few horses broke free of their reins and were galloping down the street, chased by their furious owners. How quickly panic took over the frightened residents.

The carriage ground to a halt. Emilie pushed open the carriage door and scrambled outside. Lucien and Violette joined her, and they stood by the side of the road, watching the scene unfold before them like spectators to a disaster. Ash and volcanic dust rained down on their heads while the ground continued to shake.

“We really must get out of here,” said Lucien as the party climbed back into the carriage.

The driver cracked his whip, and the horses trotted across the stone bridge that crossed the rivière Roxelane and then proceeded north for several miles along the coast before turning east onto a dirt road bounded by coconut palms and bamboo that led to the tiny hamlet of Saint-Philomène, where Emilie’s father’s plantation was located. As they climbed the western slopes of Mount Pelée, an ominous smell filled the air. It was not a burning kind of smell, like the occasional fumes that drifted down from the Guérin sugar factory across the savannah, but a different kind of smell, like rotten eggs. Emilie pressed her handkerchief to her nose and mouth. Lucien slipped his arm over her shoulders, but she again stiffened at his touch. As the carriage made its way down the dirt road, an uncomfortable silence followed, during which time Emilie pondered her dilemma. She had to find a way to break off her engagement without causing a scandal. But it would not be easy. No young woman of her social class had ever broken an engagement and survived the resulting gossip and slander. The scandal would crush her parents and brand her a social outcast. Her mind raced as she searched for a solution, but it seemed hopeless. She gazed up at the summit of Mount Pelée, but an ominous film of clouds blotted out the moon, reducing her world to utter darkness.

Chapter 2

Tuesday, April 22

The next morning Emilie awoke to the voices of the field workers reverberating through the jalousies. There was a clattering of dishes from the outside kitchen, and a rooster crowed in the henhouse. A memory of the previous night’s fiasco flitted through her mind, and it all came flooding back. Pain gripped her, and a lump formed in her throat. In one fateful moment, her entire world had collapsed. She glanced over at the clock and groaned. Already seven o’clock. Her brother, Maurice, was waiting for her out in the fields.

Downstairs she found a copy of Les Colonies lying on the dining room table and leafed through the pages. Oddly, the newspaper seemed to be making light of the previous night’s disturbance, as if it had been a burlesque performance gone wrong. The editor, Marius Hurard, wrote that “the trembling in the theater served to heighten the dramatic tension on the stage” and “the flashes of light on top of the mountain were more reminiscent of a Bastille Day celebration than an actual volcanic eruption” and “the only thing missing to make the evening more celebratory was the municipal band playing the Marsellaise.” Emilie furrowed her brow. Why no mention of the tremors? Why no mention of the ash clouds? Why no mention of the panic in the streets? What are they hiding? She threw the newspaper down in disgust.

Behind her she heard a shuffling noise. Her old nurse, Da Rosette, came hobbling into the dining room bearing a breakfast tray and a pot of coffee. She was wearing her usual bright madras skirt over a white chemise, and on her head was a yellow turban. Rosette Desrivières, or Da Rosette, as she was called, had worked for the Dujon family for more than fifty years. She was the mainstay of the household. Rising in rank from cook to house servant to nanny, she had almost single-handedly raised two generations of Dujon children. Though she was getting on in years and needed a cane to walk, her hearing was still acute, and few details escaped her sharp eyes. It was almost impossible to keep a secret from Da Rosette. It pained Emilie that she would have to tell her nurse the truth about Lucien.

“What happened, doudou?” said Da Rosette, setting the tray down on the table. “You look like you have seen a zombie.”

“Something terrible happened last night.”

“You mean the tremors?”

“There was fire on the mountain. It was terrifying.”

Da Rosette frowned. “All that drinking and carousing makes Father Pelée angry. But don’t worry, cocotte, soon he will go back to sleep. Pelée is our protector, not our destroyer.” She picked up a papaya and began to carve it with a pearl-handled knife. “The spirits dance a caleinda and play the tam-tam and drink too much rum, and the Bon Dieu gets angry.”

“That’s just superstition,” said Emilie. “There has to be a scientific reason for what happened. It’s not the spirits that are making fire on the mountain, but something much worse. But something else happened last night. Something awful . . .”

“Why the long face?” said Da Rosette. “Soon you will be the happiest bride in all Madinina. When the time comes, I’ll take out the best linen and china, and you’ll wear your grandmother’s lace dress and pearls. Grandma Loulou would be so proud of you.”

Emilie stared at her nurse. “Da, there’s something I have to tell you. I found out Lucien has another doudou. He doesn’t love me anymore.”

The old woman looked shocked.

Emilie continued, “Da, do you remember the old saying: ‘Even if you paid him all the money in the world, a monkey has enough sense not to climb a thorny tree’?”

The elderly woman put down the papaya. “M. Monplaisir is rich. He will make a wonderful husband for you. Don’t talk such foolishness! Of course he loves you.”

Emilie shook her head. “I know he loves someone else. I can’t marry Lucien. It would be a terrible mistake . . .”

The old woman grabbed her wrist. “Shh! Don’t talk like that! Of course Lucien loves you. No man is perfect, but a good wife always looks away from her husband’s faults. Does the crab expect the mouse to soar like an eagle? The Bon Dieu has done you a great favor in giving you a rich husband. You should be thankful, or you will bring

a terrible curse on your head. Do you want to end up marrying a zombie?”

Feeling vindicated, Da Rosette got up and began sweeping the floor, banging into furniture, clattering the dishes, and making a ruckus to show her displeasure. Her thin, bony hands clutched the broom like the claws of a raven. When she opened the door to sweep the dirt outside, she uttered a terrifying shriek.

Emilie rushed to her side. Outside, a huge crab with one leg missing was scampering down the path, trying to escape. Emilie felt instant pity for the creature. It had probably escaped from one of the workers’ barrels. The field hands had a custom of fattening up their crabs by feeding them mangoes, green peppers, and maize before boiling them alive and stewing them in their favorite dish, matoutou de crabe, an island specialty.

Before Emilie could stop her, Da Rosette lifted up the broom and began to beat the crab without mercy until the poor creature scurried away into the bush.

“Go away, wretched beast!” cried Da Rosette, shaking her fist.

“Da, why did you treat the crab so cruelly?”

“That was no crab,” said her nurse. “It was a little zombie. Tonight I will burn a candle to ward it away and to scare the others away.”

Emilie grabbed the broom out of her hands. “Da, sometimes a crab is just a crab. Leave it alone!”

But the old woman would not listen. She waved Emilie off and began rearranging the dishes, singing one of her spirituals with renewed fervor. It was Da Rosette’s way of shutting out all conversation. Emilie hated when she was like that; it was impossible to talk to her. Anyway, she would never see things Emilie’s way, especially about Lucien. Although Da Rosette’s heart was pure, she lived in a world of superstition, fear, and irrational beliefs tied to voodoo. It affected everything she did. When Emilie was little, Da Rosette would fill her head with all sorts of stories about voodoo and spirits. And whenever Emilie would stumble across strange voodoo ritualistic items such as a toad with its mouth chained shut, slaughtered chickens, or miniature black coffins filled with graveyard dirt, Da Rosette would jerk her away while crossing herself, warning her that she must never step over a quimbois (as a voodoo item was called in Martinique) or it would bring trouble. To Da Rosette, canceling a wedding was tantamount to bringing a curse. It was simply not done. She was stuck in her ways and would never change. Emilie looked at her old nurse with pity, resigning herself to the fact that in the matter of Lucien Monplaisir, she was entirely alone.

Island on Fire

Island on Fire